From the Western Frontier to the Digital Frontier: A History of the State Law Library

Director Amy Small researched and compiled this article for the Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society. It originally appeared in vol. 8, no. 4 in Summer 2019 of the TSCHS.

“[A] lawyer without books would be like a workman without tools.”[1]

– Thomas Jefferson

1840–1892: The Early Years

During the Republic of Texas and the early days of statehood, legal materials were scarce. Public law libraries were unheard of and practitioners primarily depended on private collections. While some private collections were dazzling in scope, such as John Hemphill’s 2,400-volume collection,[2] even the collections of respected and successful lawyers were more often meager holdings of fewer than 100 books.[3] In one astonishing case, the chief justice of Brazoria County opted to spend “considerable sums on clothes and liquor” and owned only two law books at the time of his death.[4] Even if they owned numerous books, frontier attorneys and judges were in practice limited to the number of books that they could stuff into their saddlebags.[5]

The paucity of Republic-era law libraries may have been as much due to the difficulty of having books delivered and distributed as it was to the relatively small number of legal publishers. In a letter to a friend, Chief Justice John Hemphill related a book-delivery mishap worthy of the Wild West: “These books were landed at Linnville and from thence carried off by the Indians in their late incursion. They were recaptured afterward on the Plumb Creek Battleground and most of them sent to Victoria.”[6] The books in question, a volume of the United States Supreme Court Reports and an English summary of Spanish law, suffered considerably before making their way back to the judge. The books were “strung to the Indians’ saddles by strings run through the volumes.”[7] The book thieves forced a woman captured in the same heist to read aloud from the volumes for their amusement, which caused an observer to declare that “[d]eath would have been preferable.”[8] Once all parties tired of that, several pages were torn out and used as cigarette rolling papers.[9]

Whatever the cause, the scarcity of legal materials is reflected in the quality of the scholarship in legal opinions of the time. Chief Justice Thomas J. Rusk’s opinions from 1840, collected in Dallam’s Reports, did not cite any legal authorities whatsoever. In The History of the Supreme Court of the State of Texas, J. H. Davenport posits that this could be due to the fact that “in the infancy of the Republic there were practically no authorities accessible to the court,” rather than a lack of “great learning” on Chief Justice Rusk’s part, as a contemporaneous biographer suggested.[10] Other opinions from this time period explicitly lament the lack of access to legal resources. Several of Chief Justice Hemphill’s opinions qualify his decisions due to “the want of authorities.”[11] In one case, Republic v. Dewees, the Court declined to rule on a point of law entirely because they felt they could not properly consider it “without Books and the assistance of counsel.”[12]

The Texas Supreme Court was formally established in 1846 without an accompanying library or devoted research materials.[13] The new Supreme Court justices surely must have been plagued by the same problems that justices in the Republic of Texas faced because in 1849 Attorney General John W. Harris delivered a report to Governor George T. Wood containing an impassioned plea for the acquisition of a law library. Harris recognized the danger that inadequate legal resources posed to the fledgling body of civil law in Texas.

The system which is being formed by the decisions of our Supreme Court, when tested by the legal lights of other states and countries may be found (in many important particulars,) at variance with some of the longest established principles of the law.[14]

Creating and perpetuating a body of law based on faulty legal fundamentals, he warned, endangered “thousands of innocent citizens.”[15] He urged immediate action to supply the Supreme Court with materials so that the Court could adjudicate correctly from that point forward. “Remedies come too late when the mischief has already been done.”[16]

His request did not fall on deaf ears. The following year, the Legislature issued a joint resolution granting the Supreme Court an appropriation of $100 “for the purchase of thirteen volumes of a collection of the laws, decrees, edicts, regulations, etc.”[17] Four short years later, in 1854, the Legislature transferred the Secretary of State's collection of law books to the Supreme Court and appropriated the eye-popping sum of $15,000 for the purchase of books.[18]

To put the size of that budget and its purchasing power into perspective, the private law library of New Orleans attorney Henry Adams Bullard was auctioned in 1851, bringing in $362.91 for the 411 volumes in the collection.[19] Fifteen thousand dollars was enough to procure a world-class law library.

The responsibility for purchasing material for the Library of the Supreme Court rested with the Chief Justice. At the time of this windfall, that position was held by John Hemphill, owner of the fabulously extensive legal collection referenced above. Chief Justice Hemphill’s involvement in the development of early Texas law cannot be overstated. As a legal scholar, he had a particular passion for Spanish and Mexican law. He was conversant in Spanish and helped to incorporate concepts from Spanish law, such as homestead exemptions and community property, into the Texas Constitution.[20] His interest in Spanish civil law is reflected in the purchases of this era; a Supreme Court Library catalog from 1880 shows that Spanish law titles make up a third of the civil law collection and were all purchased prior to Hemphill’s departure from the Court in 1858.[21]

From this point, the Supreme Court Library began to take shape with new guidelines issued from the Legislature every few years. Beginning in 1860, the Secretary of State was required to furnish all three branch libraries of the Supreme Court with sufficient copies of case reports, statutes, and digests so that the individual judges plus every branch library would receive a complete set of each. In 1864, the clerk of the Court was mandated to be the librarian, responsible for “keeping and preserving the books of the Supreme Court.”[22] The duties of the clerk/librarian were further expanded in 1866 to include the creation of catalogs of the libraries’ books. The 1866 bill also required that the libraries be open to public use.[23] The lack of any other law libraries open to the public in the area meant that local attorneys and law students often stopped in to discuss and debate, creating a convivial environment for the keen legal minds of the time.

By 1882, these developments had transformed the Supreme Court Library from a nonentity to a celebrated collection of “all the learning—continental, English, and American.”[24]

1892–1959: Stretched Thin

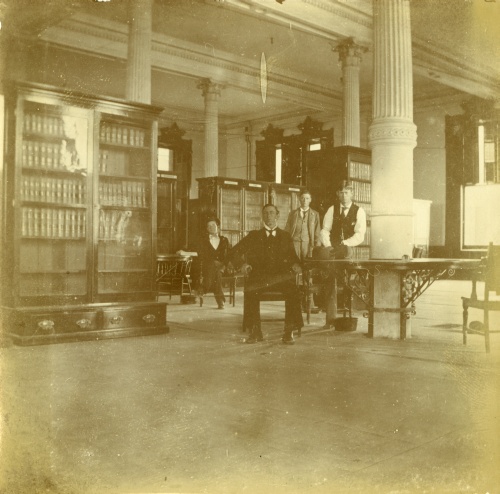

In 1892, the Galveston and Tyler branches of the Supreme Court and its libraries were disbanded by the Legislature, and the Court settled into its permanent home in Austin.[25] The contents of the now-defunct branches were consolidated into one Supreme Court Library, which was housed in the north wing of the newly constructed Capitol. The Supreme Court Library and the Texas State Library shared a beautiful space which is now home to the Legislative Reference Library.

After the succession of legislation that formalized the Supreme Court Library in the 1860s, the Library remained mostly untouched by the Legislature until the 1950s. The Library did not receive any further large infusions of money, and its day-to-day operations were left in the capable hands of its librarian, Lawrence K. Smoot. Although the clerk of the Supreme Court was statutorily designated as the librarian, then-clerk Dr. Charles S. Morse decided that he much preferred to hire someone to serve as a librarian to manage the Court Library. Morse hired Smoot as a librarian in 1896, marking the beginning of a long career with the Supreme Court. In a 2011 Senate Resolution honoring his daughter, Jane Smoot, he was recognized as the longest-tenured state employee ever, with sixty-six years of service to the state.[26] The one major instance in which the Legislature meddled with Library operations came in the 1907 legislative session. The House of Representatives adopted a resolution to keep the Supreme Court Library open from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., seven days a week, with a mere pittance appropriated for “additional help."[27] Ever dedicated, Smoot manned the Library day and night by himself for months, straining his health to the point that he needed an entire year to recover.

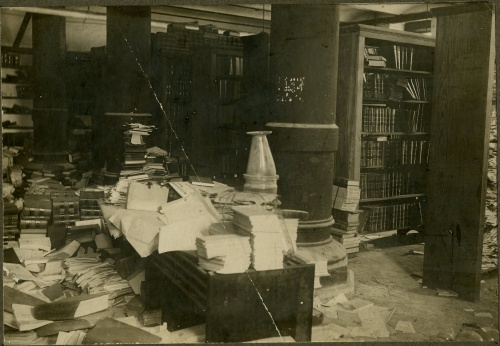

Smoot recalls the general disorder that greeted him in his early days on the job. “The judges would send a porter to the library to locate a book. If the book was missing, the porter would just bring the book next to the one that was missing.”[28] This lackadaisical attitude towards library resources can be seen in photographs of the Capitol basement around the turn of the century. Books are piled on the ground, spilling into disorderly heaps of haphazard pages.

A constitutional amendment adopted in 1945 increased the number of Supreme Court justices from three to nine.[29] The newly tripled Court, plus the additional support staff, placed further strain on library resources. The number of library staff did not increase proportionally, stretching the one librarian and one porter that the Legislature allotted to the Supreme Court even thinner. By the 1950s, stagnant funding and suffocating overcrowding in the Capitol had taken its toll on the Supreme Court Library. Books and records were stored in disarray in barns in north Austin, literally piled to the rafters.[30] The justices’ offices were separated into two groups on the third and fourth floors of the Capitol, while the library itself was inconveniently still located on the second floor.[31] The library collection was scattered throughout hallways, with a makeshift “huddle room” on the third floor. Valuable volumes had to be kept in secure locations to protect them from theft,[32] possibly by attorneys who feared never being able to find a specific book again if they returned it.[33] In this state, the library was all but useless, and in fact was rarely used by members of the Court. Justice Joe Greenhill recalls that he “certainly never checked out a book”[34] from the “poor excuse for a library.”[35]

Recognizing the desperate need for adequate facilities, Representative Bill Daniel led a charge in the Legislature for the construction of additional buildings in the Capitol area to house the Courts, the State Library, and the Office of the Attorney General. His initial attempts were not successful, but Representative Daniel was undeterred, and a constitutional amendment approving the use of Confederate pension funds for a new Supreme Court Building was finally approved by voters six years later in 1954.[36] The Supreme Court Building was completed in 1959.

While the new building temporarily gave the Library some much-needed space, it did not address any of the deeper problems the library was facing. The Legislature had neglected to appropriate money for any furniture or additional staff for the new library. Frances Horton, the long-suffering librarian since 1947, soldiered on with only a porter to assist her with book repairs and shelving. She regularly exhausted her book budget partway through the year and had no funds for treatises or textbooks.[37]

The beleaguered Library found a champion in Jack Pope upon his election to the Supreme Court in 1964. Justice Pope found the Library to be sorely lacking compared to the Bexar County Law Library at his previous post as Court of Appeals Justice in San Antonio. Upon joining the high court, he expressed shock that everyone seemed satisfied with such a poorly-maintained library. His dismay prompted Chief Justice Robert Calvert to ask him to assume administrative oversight of the Library in 1969. Justice Pope immediately got to work and took his concerns directly to the Legislature. He recalled a particularly effective appearance before the Senate Committee in his interview in A Texas Supreme Court Trilogy:

I asked Chief Justice Calvert if he would consent to my appearing before the Senate Committee to request funds, and he heartily agreed. I appeared and displayed to the Committee a textbook published in 1920 by Professor Cooley. I told the Committee that I was showing them the most recent work in the Supreme Court Library about constitutional law and that most law firms in Texas had more recent and scholarly materials than the Texas Supreme Court.[38]

Justice Pope worked closely with Frances Horton to develop a plan to improve the Library’s standing. A critical component of this plan was the solicitation of evaluations of the Library’s collection and staff from local professional librarians. Horton and Pope reached out to Alfred J. Coco, law librarian at the Bates School of Law at the University of Houston; Professor Roy Mersky from the Tarlton Law Library at the University of Texas School of Law; and Dr. Dorman Winfrey and Lee Brawner of the Texas State Library, for their expertise. To no one’s surprise, the evaluations found that the Library was “in desperate need of additional staff” and that the budget was “wholly inadequate” to maintain a collection that had value but was sadly neglected.[39]

Thinking that bringing the Library out from under the shadows of the Supreme Court might improve its standing, Justice Pope and John Onion, Presiding Judge of the Court of Criminal Appeals, asked State Senator Jack Hightower and Representative Don Cavness to sponsor a bill changing the name of the Supreme Court Library to the State Law Library. The critical shortcomings described in the Library evaluations spurred the Legislature to act, and the bill sailed through both chambers without a single dissenting vote.[40] The legislation also had the purpose of expanding the Library’s patron base to include citizens of the state.

On June 8, 1971, Governor John Connally, once a part-time employee in the Supreme Court Library,[41] signed the bill creating the State Law Library as an independent agency.

1971–2004: A New Beginning

The first order of business for the new agency was to get the Library’s collection back into shape. To do so, the Library needed three things: more staff, a systematic analysis of what the collection had and what it lacked, and funding.

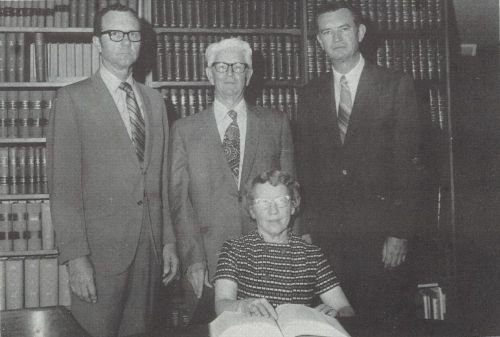

The newly formed Board of Directors, consisting of Justice Jack Pope from the Supreme Court, Judge Wendell Odom from the Court of Criminal Appeals, and Alfred Walker from the Office of the Attorney General, approved the hire of Jane Olm as Assistant Librarian. Olm brought to the job four years of experience at the University of Texas’s Tarlton Law Library and a master’s degree, making her the first professionally trained librarian in the Library’s history. She also brought her personal electric typewriter. As of 1968, the new Library had no catalog[42] and the staff had no real grasp of what the collection contained, presenting obvious problems for Library patrons. Jane Olm and her typewriter set to work on the necessary but monumental task of creating a card catalog from scratch. In addition to solving basic usability problems, a complete catalog would allow the staff to identify areas of the collection that needed development and to submit targeted requests for funding to the Legislature.

As far as funding, the development of the state budget for the 1972–73 biennium was taking place at the same time that the bill establishing the State Law Library as a separate agency was moving through the Legislature. The initial appropriations bill granted the Supreme Court $20,000 per year for the operation of the Law Library in 1972 and 1973.[43] Governor Preston Smith vetoed the entirety of the 1973 appropriations,[44] causing this portion of the budget discussions to be deferred to a special session that would not start for a full year. Justice Pope seized upon this extra time and again came to the Library’s rescue. His advocacy to the Legislature resulted in a total of $106,173 being set aside from the budgets of the Supreme Court, the Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Office of the Attorney General for the operation of the State Law Library in the 1973 fiscal year.[45] This huge increase in budget, along with a $30,538 grant from the Criminal Justice Council, permitted the Library to purchase six hundred new titles and fill gaps in the collection that had accrued over time.

Frances Horton retired in February of 1972, concluding twenty-five years as the steadfast if often underappreciated law librarian for the State of Texas. The Library’s Board offered the Director position to Marian Boner, who readily accepted. Boner was an attorney, Associate Professor at the University of Texas School of Law, Reference Librarian at Tarlton Law Library, and according to Jane Olm, “a bundle of energy” and a “tireless legal scholar.”[46]

Boner’s enthusiasm was apparent in the incredible headway Library staff made in her first two years as Director. The Library hired two additional librarians, a cataloger, and an acquisitions librarian, doubling the size of the professional staff almost overnight. The collection was carefully evaluated and more than 9,000 out-of-date or duplicate volumes were discarded or sold.[47] She acquired modern equipment, such as electric typewriters, an ultrafiche reader/printer, a coin-operated Xerox machine, and an electric adding machine, for the use of staff and patrons. The Library extended its hours to remain open in the evenings. The Library also took on the responsibility of assisting incarcerated Texans with locating copies of their case files, a huge task that formerly fell to the State Bar. During this era, Boner somehow also managed to find the time to write A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History: Sources and Documentation, a thoroughly researched overview of the evolution of Texas’s legal framework and relevant resources.

Boner made concerted efforts to increase awareness of the Library’s new and improved services and collection. She published an update on the Library’s progress in the Texas Bar Journal in 1976, explaining what the newly established agency had to offer and emphasizing its utility to practicing attorneys. She urged attorneys from all across Texas to visit the Library to “get acquainted with its collection.”[48]

The net effect of many of the changes that Boner implemented was to transform the Library from a mere collection of books to a research facility that was managed by professionals. The librarians she hired had been educated in the most effective ways to match patrons with the information they were seeking, which heightened the services that patrons could expect to receive. She and her two successors, Jim Hambleton and Kay Schlueter, were all active in regional and national law librarian organizations. They held leadership roles in these organizations and spoke at conferences, raising the profile of the Library as a truly professional entity.

Jim Hambleton succeeded Marian Boner as Director in 1981. Like Boner, Hambleton was an attorney and former Head of Public Services at UT’s Tarlton Law Library. Hambleton’s primary professional interests were exploring the quirks of Texas law and considering how attorneys and librarians could use new computing technology to improve access to information. In 1983, he correctly predicted that “[t]he day will arrive when most attorneys do their legal research at a terminal beside their desk, at a considerable saving of time and with greater accuracy than presently.”[49] As Director of the State Law Library, he did his part to encourage the legal community to embrace computers. His direction set an enduring precedent in the Library: it would adopt cutting-edge technology that would allow patrons to conduct more efficient and effective research. In 1984, the very first year that personal computers were available through a state purchasing contract, Hambleton bought two for the Library.[50] It was also during his tenure as Director that the Library acquired Westlaw and Dialog terminals.

Hambleton was also an enthusiastic and prolific author. During his time as Director, he published frequently, mostly in the Texas Bar Journal, as author or co-author of over twenty articles from 1982 to 1985. He had a keen mind for discussing aspects of legal research that would interest and affect practicing attorneys. As a representative of the State Law Library, his constant presence in legal periodicals reflected well on the Library as a serious and professional center of legal thought. He, along with librarian Karl Gruben, edited the second edition of Marian Boner’s Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History.

The Library’s success in recreating itself as a relevant and vital member of the legal community was tempered by the fact that it was once again housed in inadequate and crumbling facilities. The Supreme Court Building housing the Library was showing its age. The building itself was falling apart and staff and patrons were regularly startled by exploding fluorescent light fixtures.[51] An outdated electrical system and asbestos ceiling posed additional hazards.[52] The Library was bursting at the seams with hundreds of new titles and no amount of conversion to microfiche alleviated the need for more space. In time, the Library even ran out of room for microfiche storage.

To address these concerns, the Legislature authorized the construction of the Price Daniel Building and the renovation of the Supreme Court Building with new library space in 1985. By the time construction broke ground in May of 1991, Kay Schlueter had risen to the role of Director. The renovations required the relocation of the books and equipment that the Library had so carefully acquired in recent years. The temporary location in the new Price Daniel Building was not large enough to accommodate the 110,000 to 120,000 volumes the Library now owned, and so the majority of the collection was housed in a makeshift storage area in a parking garage. The garage was plagued with problems: horrendous smells, fluctuating temperatures, and mosquitoes.[53] Worst of all, patrons were frustrated by their inability to access over half of the Library’s collection. Library staff suffered these professional indignities for two years, bringing to mind the disjointed and chaotic conditions that the Supreme Court Library endured in the 1950s.

In another stroke of misfortune reminiscent of the mid-century move from the Capitol to the Supreme Court Building, the Legislature yet again did not provide funding for furniture for the new space. Kay Schlueter rallied supporters of the Library to form the Friends of the State Law Library, known as FOSLL. FOSLL organized a fundraising effort whereby donors could honor loved ones by etching their names on brass dedicatory plaques on the chairs and tables that their donations made possible. In Schlueter’s own words:

When planning our renovated space and moving back into our building several years ago, we wanted to find a way to make this more than just another state office building. We wanted to recapture the warmth of our old surroundings and to have some obvious ties to the history and development of our legal system. We couldn't think of a more appropriate way of doing this than recognizing the men and women who have shaped our system through the years.[54]

These pieces of furniture remain a lovely feature of the Library even today, and the occasional visits by donors and their families to see their chairs continue to delight the staff.

When not enduring the horrors of the parking garage workspace, Schlueter’s focus as Director was to continue Marian Boner’s outreach efforts to the legal community. Schlueter assembled a strong network of Library advocates and volunteers. The Library regularly drew more than 1,000 volunteer hours per year. Volunteers lightened the burden of clerical work and created the Library’s first website. FOSLL grew into a fundraising powerhouse, capable of raising donations equal to about 25 percent of the Library’s annual appropriations.[55] Schlueter also involved county law libraries in the Library’s services for the first time. Her push to have local government law libraries included in the first statewide LexisNexis and Westlaw contracts resulted in incredible cost savings at the local level. She organized and hosted the first meeting of the Texas County Law Librarians, which served to encourage cooperation and collaboration among the state’s government law libraries.

The dedication ceremony for the new State Law Library facilities took place on May 27, 1993. The ceremony’s program reflected the support system that Schlueter and her predecessors had built. Representatives from all corners of the local legal community spoke in celebration of the Library and the ideals of justice and knowledge that it represented: Supreme Court Justice Nathan Hecht, Court of Criminal Appeals Presiding Judge Michael McCormick, State Solicitor Renea Hicks, former Director Jim Hambleton, Judge John Powers of the Third Court of Appeals, and local law firm librarian Joan O’Mara.

Tony Estrada replaced Kay Schlueter as Director in 2002 and continued FOSLL and the Library’s volunteer program as an important support system for the Library. He also honored Jim Hambleton’s tradition of pursuing technology to improve the dissemination of information by initiating a historical statutes digitization project. Supported by a grant from the Litigation Section of the State Bar of Texas, the Library scanned the complete text of the 1879–1925 Revised Civil Statutes and posted them on the Library’s website to be used by the public for free.

2004–Present: The Digital Era

Dale Propp became the Director of the Library in May of 2007. The first challenge he faced was the continued disconnect between the rising costs of keeping the Library’s print collection up to date and the amount of funding provided by the Legislature. For years, the Library saw publishing costs increase steeply without a commensurate increase in budget. In the Administrator’s Statement for the Library’s FY 2008-09 Legislative Appropriations Request, Propp stated that “[i]n a comparison between the years 2000 and 2004, publishing costs have increased 38 percent.”[56] Over that same time period, total funding for the Library decreased by 7.5 percent.

This ever-present problem for the Library continued mounting in the 2010–11 biennium when a statewide fiscal setback caused by the 2008 recession required all state agencies to cut their budgets by 5 percent. The budget crunch reached a critical point in 2011 with the Legislature’s proposed budget for fiscal years 2012–13. The first draft of the state budget gave the State Law Library zero dollars in appropriated funds,[57] prompting fears that the Library would be eliminated as an agency altogether. Thanks to the support of the legal community and key legislative leaders who understood the Library’s value, the Library was eventually funded but received a devastating 22 percent cut to its operating budget.[58]

The only way for the Library to continue functioning on such a shoestring budget was to render deep cuts to the Library’s print collection. In 2011, the Library was forced to cancel subscriptions for many treatises and periodicals. These cuts are still felt to this day, as in the ensuing years the Library’s funding for print materials would never keep pace with rising costs, let alone increase enough to allow for the renewal of canceled subscriptions.

A common refrain during the fraught budget hearings leading up to the 82nd Legislative Session was: If Austin has so many other law libraries—why do we need the State Law Library? At first glance, Austin does have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to law libraries: Travis County Law Library, Tarlton Law Library at the University of Texas, the Legislative Reference Library, and the State Law Library. However, each library has a unique focus and serves the public in a distinct way. The other libraries serve the needs of local citizens (Travis County Law Library), the Legislature (Legislative Reference Library), and law students and legal scholars (Tarlton Law Library), and they do it exceedingly well. However, none of these libraries is mandated to serve the staff of state agencies, the practicing legal community, and the general public on a statewide basis in the way the State Law Library is.

Understanding that the library needed to distinguish itself among the other law libraries in Austin and recognizing that recent advances in technology finally made true statewide support possible, in 2013 Propp began the development of an initiative to make the Library’s resources available from a distance and expand its reach beyond the Austin city limits. Prior to this time, the Library would field calls and letters from citizens throughout the state, but the ways in which librarians could assist those remote patrons was limited. Patrons outside the Austin area certainly didn’t have the ability to use the Library’s resources to research on their own.

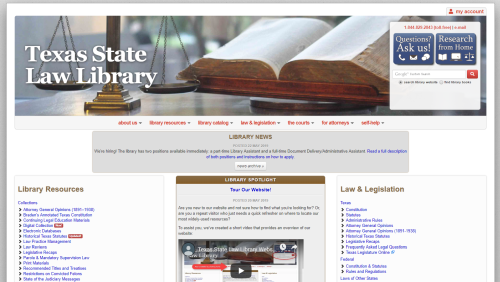

A complete overhaul of the Library’s website in 2013 transformed it from a simple page that only offered basic details about the Library’s services to a sophisticated site that contained usable legal information. Librarians began using software called LibGuides to create research guides on topics that members of the public frequently asked about, such as common law marriage and small claims court. These research guides link to the text of the law itself, as well as explanatory articles which put the legal jargon of the statutes into context. At the time of their debut in January of 2013, the Library offered guides on only six topics: Common Law Marriage, Historical Texas Statutes, Historical Texas Court Rules, Name Changes, Occupational Drivers Licenses, and Small Claims Court.[59] Merely a year later, there were four times as many guides, garnering thirty-five times the number of monthly views. The Library currently offers sixty guides that receive approximately 70,000 total monthly visits.

In an effort to increase the amount of legal information available through the website, Propp continued and expanded Tony Estrada’s historical statute digitization initiative, eventually securing grant funding and copyright permission to digitize the Library’s historical statutes through 1984. Before the completion of this project, tracking these statutes down was difficult— only Baylor University and the State Law Library held a complete collection.

The crown jewel in the Library’s efforts to make reputable legal information widely available is the Remote Access Program, established in 2015. As legal publishers began producing e-books and online databases, Propp recognized an opportunity to use these resources to support Texans in far-flung parts of the state. The first stage of the program involved getting permission from publishers to allow the Library to make their products available remotely. Assistant Director Leslie Prather-Forbis’s careful and patient negotiations convinced numerous publishers that allowing the public to access their materials through the Library would not only not affect their profits, but it would also generate immense goodwill with the legal community.

Next, Library staff needed a way to control access to these resources and limit it to registered patrons. The Library switched public catalog systems in 2015, moving from the State Library-controlled SirsiDynix to Koha, an open-source, web-based application. Koha offered many new features that SirsiDynix lacked, including online patron self-registration. Self-registration reduced barriers to registering for a Library account, as patrons no longer had to come to the Library in person to sign up. It also offered a way for librarians to gatekeep access to the resources they planned to offer remotely.

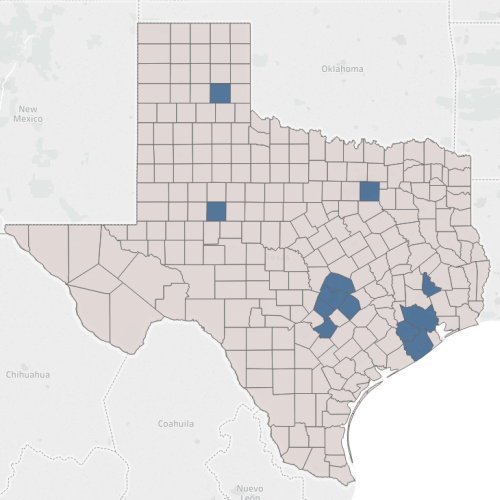

With all the details worked out, the Library could now curate a digital collection for remote use. Prather-Forbis, who also served as Acquisitions Librarian, selected and purchased approximately five hundred e-books, ranging from self-help titles for the legal novice to specialized practice guides and treatises for attorneys. The contracts she negotiated for electronic access to legal databases were put into place. Suddenly, Library patrons had a wealth of high-quality resources available to them outside the Library’s walls. At the time of these purchases, only 59 of Texas’s 254 counties maintained any type of law library collection, not all of which were open to the public or staffed by professionals who could assist with research. Rural Texans who could not afford an attorney were often left with few ways to obtain accurate legal information. The digital resources the Library provided at no charge to all Texans, regardless of their economic status, opened up a whole new world of information.

To demonstrate the sheer scale of the volume of information available to State Law Library patrons through the Remote Access Program, one must only look at the Library’s collection of legal periodicals throughout time. In 1912, the Supreme Court Library did not receive any current periodicals.[60] At the same time, the University of Texas only received four legal periodicals.[61] Today, HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library includes 2,707 titles that patrons can access using their State Law Library account, at any time of day or night.

Looking to the Future

Beginning in 2013, Propp approached the Legislature each session with requests for more stable funding for the Remote Access Program. Even as usage of the program climbed steadily, indicating a real demand for the service, the Legislature declined to grant the additional funding that would sustain the program. Finally, in 2019, the Library received the good news that the Legislature had at last appropriated funds to support its efforts to provide digital legal resources.

The Library also received funding to continue the digitization project and make additional important Texas historical texts freely available via the State Law Library website. Former Library Director Marian Boner’s classic A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History, including links to digital editions of many of the key resources highlighted, is slated for inclusion in this project.

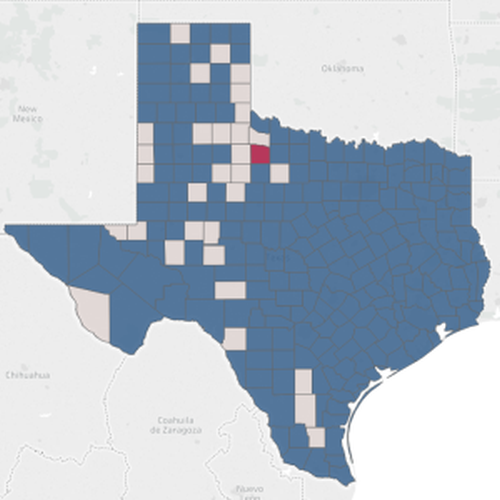

Today, the Library has had 14,721 users register from 223 of 254 counties in Texas, indicating considerable success in efforts to support citizens statewide. It is doubtful that visitors to the Supreme Court Library 150 years ago could ever have imagined the size and reach of the modern State Law Library’s collection. The Library is committed to continuing the traditions of excellence established by previous Supreme Court librarians and State Law Library Directors, albeit with a wider audience.

Footnotes

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Turpin, 5 February 1769, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 24.

- ^ Journals of the Sixth Congress of the Republic of Texas 1841–1842, December 20, 1841, 198. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/CongressJournals/06/houseJournalsCon6_201.pdf#page=2.

- ^ William Ransom Hogan, The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1946; Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2006), 252. References are to the Texas State Historical Association edition.

- ^ Ibid., 251–52.

- ^ Ibid, 251.

- ^ John Hemphill to Washington D. Miller, 24 August 1840, Washington Daniel Miller Papers, Texas State Library and Archives.

- ^ Mary A. Maverick, Memories of Mary A. Maverick (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 44.

- ^ Z. N. Morrell, Flowers and Fruits in the Wilderness: or, Thirty Six Years in Texas and Two Winters in Honduras (Waco, TX: Baylor University, 1972), 130–31.

- ^ Maverick, 44.

- ^ J. H. Davenport, The History of the Supreme Court of the State of Texas (Austin: Southern Law Book Publishers, 1917), 15.

- ^ Smith v. Townsend, Dallam 569, 570 (Tex. 1844).

- ^ Republic v. Dewees (Tex. 1845), 65 Texas L. Rev. 382, 405 (Paulsen rep. 1986).

- ^ An Act to Organize the Supreme Court of the State of Texas, approved May 12, 1846, 1st Leg., R.S., 1846, Laws of the State of Texas 249, reprinted in 2 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 1555. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6726/m1/1559/.

- ^ Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Texas, 3rd sess., October 27, 1849, 44. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/HouseJournals/3/houseJournal3rdLeg001.pdf#page=38.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Joint Resolution Making an Appropriation for the Purchase of Certain Books for the Use of the Supreme Court, approved February 11, 1850, 3rd Leg., R.S., ch. 141, Special Laws of the Third Legislature of the State of Texas, 94, reprinted in 3 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 764. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6728/m1/768/.

- ^ An Act to Provide Books for the Use of the Supreme Court, approved February 4, 1854, 5th Leg., R.S., ch. 34, Laws of the Fifth Legislature of the State of Texas, 49, reprinted in 3 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 1493. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6728/m1/1481/.

- ^ Robert Feikema Karachuck, “A Workman’s Tools: The Library of Henry Adams Bullard,” American Journal of Legal History 42 (1998): 161.

- ^ Thomas W. Cutrer, “Hemphill, John,” Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fhe13.

- ^ Michael Widener, "The Civil Law Collection of the Texas Supreme Court," Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository, 9. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/ylss/30/.

- ^ An Act to Amend the Fourth Section of an Act to Organize the Supreme Court of the State of Texas, approved May 12, 1846, 10th Leg., 2d C.S., ch. 2, General Laws of the Tenth Legislature 3, reprinted in 5 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 809. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6727/m1/825/.

- ^ An Act to Confer the Office of Librarian on the Clerks of the Supreme Court, approved November 7, 1866, 11th Leg., R.S., ch. 105, General Laws of the State of Texas 98, reprinted in 5 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 1016. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6727/m1/1032/.

- ^ George W. Paschal, Preface to Reports of Cases Argued and Decided in the Supreme Court of the State of Texas, vol. 28 (St. Louis: Gilbert Book Company, 1882), 7.

- ^ Act approved April 13, 1892, 22nd Leg., 1st C.S., ch. 14, General Laws of Texas 19, reprinted in 10 H.P.N. Gammel, The Laws of Texas 1822–1897, 383. Available online: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6733/m1/385/.

- ^ Tex. S. Res. 546, 82nd Leg., R.S., 2011 (honoring Jane Smoot). Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/billSearch/BillDetails.cfm?legSession=82-0&billTypeDetail=SR&billnumberDetail=546.

- ^ Journal of the House of Representatives of the Regular Session of the Thirtieth Legislature of Texas, January 28, 1907, 261. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/Housejournals/30/01281907_18_253.pdf#page=9.

- ^ Jack Pope, “The Path to the Texas State Law Library: Our Forgotten Heritage” (unfinished draft, undated), 18.

- ^ Tex. S.J. Res. 8, 49th Leg., R.S., 1945 Tex. Gen. Laws 1043. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/billSearch/BillDetails.cfm?legSession=49-0&billTypeDetail=SJR&billnumberDetail=8.

- ^ David B. Gracy II, This Best but Last Chance: Representative Bill Daniel’s Fight for a State Courts and Office Buildings in Texas, 1949-1954 (Austin: Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Texas at Austin, 1995), 8.

- ^ James A. Elkins, “State Courts Housing,” Texas Bar Journal 17, no. 6 (June 1954): 385.

- ^ Ibid., 386.

- ^ Gracy, 6.

- ^ Pope, “Path to the Texas State Law Library,” 27.

- ^ Ibid., 26.

- ^ Tex. S.J. Res. 10, 53rd Leg., R.S., 1953, General and Special Laws of Texas, 1172. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/billSearch/BillDetails.cfm?legSession=53-0&billTypeDetail=SJR&billnumberDetail=10.

- ^ Jack Pope, “Addendum—Judicial Opinions & Administrative Reform, March 3, 1992,” A Texas Supreme Court Trilogy, Volume 3, ed. H.W. Brands (Austin: Jamail Center for Legal Research, 1998), 96.

- ^ Ibid., 96.

- ^ Pope, “Path to the Texas State Law Library,” 32, citing a letter from Alfred J. Coco to Frances Horton, June 6, 1969.

- ^ An Act Relating to the Creation of the State Law Library, approved June 8, 1971, 62nd Leg., R.S., enrolled vote tally: https://lrl.texas.gov/LASDOCS/62R/SB528/SB528_62R.pdf#page=23.

- ^ Pope, “Path to the Texas State Law Library,” 25.

- ^ Frances Horton to Chief Justice Robert Calvert, 18 January 1968. Robert Wilburn Calvert Papers, Texas State Library and Archives.

- ^ An Act Appropriating Money for the Support of the Judicial, Executive, and Legislative Branches of the State Government, approved June 20, 1971, 62nd Leg., R.S., ch. 1047, General and Special Laws of Texas, 3421. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/ApproBills/62_0/62_R_article01.pdf.

- ^ Veto Message of Gov. Smith, S.B. 11, 62nd Leg., R.S. (1971). Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/vetoes/62/sb11.pdf.

- ^ An Act Appropriating Money for the Support of the Judicial, Executive, and Legislative Branches of the State Government, 62nd Leg., 3d C.S., ch. 1, 1972 General and Special Laws of Texas, 15. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/ApproBills/62_3/62_3_article01.pdf.

- ^ Pope, “Path to the Texas State Law Library,” 41.

- ^ Ibid., 42.

- ^ Marian Boner, “The State Law Library: A Resource for the Practicing Bar,” Texas Bar Journal 39, no. 2 (1976): 160.

- ^ James Hambleton and David Matone, “Computers and the Law,” Arkansas Lawyer 17 (1983): 28.

- ^ James Hambleton, “FY84 Annual Report of the State Law Library,” 1997/116, Texas State Library and Archives.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Justice in Cramped Quarters,” Texas Bar Journal 54, no.10 (1991): 59.

- ^ Kay Schlueter, email message to author, June 10, 2019.

- ^ Kay Schlueter, “What You’ll Find at the State Law Library,” Texas Lawyer 8, no. 47 (February 22, 1993): 10.

- ^ Dale Propp, “FY2008-09 Legislative Appropriations Request: Administrator’s Statement,” August 4, 2006.

- ^ HB 1–Introduced, 82nd Leg., R.S., available on the Legislative Budget Board’s website: http://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/Appropriations_Bills/82/2012-13%20General%20Appropriations%20Act%20-%20House%20HB1%20Introduced.pdf.

- ^ General Appropriations Bill, approved June 17, 2011, 82nd Leg., R.S., ch. 1355, General and Special Laws of Texas, 4028. Available online: https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/ApproBills/82_0/82_R_ALL.pdf.

- ^ “Research Guides by Topic,” State Law Library, as it appeared on January 18, 2013, courtesy of the Internet Archive Wayback Machine, http://web.archive.org/web/20130118104200/http://www.sll.state.tx.us/self-help/research-guides-by-topic/.

- ^ John Boynton Kaiser, “Law and Legislative Library Conditions in Texas,” Law Library Journal 4, no. 4 (January 1912): 29.

- ^ Ibid., 30.